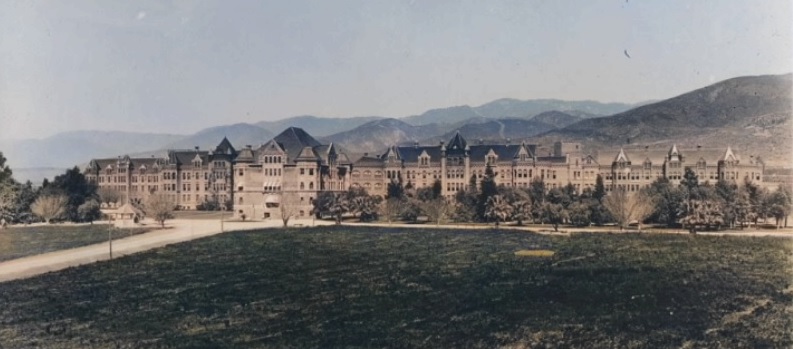

Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, the United States experienced a period of rapid growth, often called the Gilded Age. Mark Twain’s title suggested the glitz hid a grimy underside, obscuring immoral behavior encouraged by the urban immigrant underclass. In New York, a Society of the Suppression of Vice recommended An Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, obscene Literature and Articles of immoral Use. Passed in 1873, it focused on protecting young American men from prostitutes, gambling, and other temptations. Forty years later World War I began in Europe in 1914, and the hygiene focus turned to sexually transmitted infections (STI’s), or venereal disease. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. appointed Raymond Fosdick to head up the Bureau of Social Hygiene to investigate “white slavery” (sex trafficking), and illicit activities by soldiers in the army encampments protecting the US/Mexico border. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Fosdick’s attention shifted to reports from United States allies saying, “take all steps necessary to suppress prostitution in the neighborhood of military training camps...We know something of the experience through which our allies have gone. In some cases, as much as thirty-three and a third percent of the men have been made ineffective through venereal disease. We cannot afford to have any condition of that kind in connection with American troops.” Within months Congress passed the Chamberlain- Kahn Act 1918 (PL 65-193). Called the “American Plan” for public hygiene, it allowed police to arrest any woman within five miles of a military camp to test her for venereal disease, primarily syphilis, gonorrhea, and cancroid. If a woman tested positive, she could be interned in a “labor camp” until “cured.” Patton Hospital (above) in San Bernardino acted as one such place of confinement. The result was one of the longest lasting and largest scale mass quarantines in U.S. history.

Header Image: Patton State Hospital, c. 1899, from Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons

The passage of the Chamberlain Act, coupled with strong endorsements from state attorney generals led to the establishment of “morals squads” in areas within a five-mile radius of military bases, although the area often expanded when it was observed that venereal diseases often were contracted not from sex workers but from the so-called “charity girls.” The term “charity girls” became affiliated with unmarried women in the workforce whose low wages did not stretch far enough to enjoy the entertainments of the post-war era. In exchange for a man paying for these dates, women offered sexual favors, some as innocuous as a kiss on the cheek, but other intimate activities became viewed as threats to America’s war effort. The squads, therefore, would arrest women walking with a friend to the market, standing unaccompanied on the sidewalk, or any woman appearing to loiter in public. On the morning, of February 25, 1919, two deputies from the morals squad, Officer Ryan, and Officer Carls, arrested twenty-two women in Sacramento. Although only one of those arrested tested positive for a venereal disease, the women were taken to the local isolation hospital, like Patton Hospital, where they were internally examined and administered the Wasserman test to rule out syphilis. In the case of Margaret Hennessy and her friend, Mrs. Bradich, they were released that evening with fourteen other women, while six others spent the night in jail. The following morning, Marge Hennessy became the voice of the arrested as she said she valued her reputation and had been going to pick up her six-year-old son, Terry, at school. She spoke to the Sacramento Bee “to defend herself.” Although most of the charges were dismissed, she stated she was afraid to go outside for fear of being rearrested. In this case she and her son returned to their home in Alameda and to her husband, a Standard Oil worker. For others, their experience would be much more extended.

When Evelyn Travers was eighteen years old, her father Jack Travers died unexpectedly on January 27, 1918, at the age of forty-four. Born of immigrant Irish parents in 1875 he arrived in San Francisco before the turn of the century and worked his way up to steward at the local emergency hospital. Evelyn, her younger sister Thelma and their mother, Georgiana faced a crisis so dire that a Benefit Ball was held on March 5 to raise money for the family. By 1919 both Evelyn, now eighteen years old, and Thelma, now sixteen worked as “hello girls.” Since World War I many women operated the local switchboards and put through calls on the local party lines. However, in late fall, 1919 Evelyn accused of “loitering” as she walked home. Later, the arresting officer reported she was picked up in a house where she was a prostitute. The “morals squad” arrested her for “vagrancy” and sent her to the isolation hospital to be detained under the tenets of the Chamberlain Act. There she was incarcerated, threatened with arrest, and subjected to an internal examination, after which she was diagnosed with two venereal diseases, and put to work. At her hearing, she pleaded “not guilty” and waived a jury trial. She remained in the hospital against her will and was treated with the current medicines, usually including mercury injections. On May 9, 1920, the San Francisco Examiner reported her release from the hospital on a writ of habeas corpus. Despite her legal efforts, she was back in court on July 29, 1920. Although her medical tests had been negative, the court remanded her back to the hospital and refused to hear the case again on August 24, 1920. You may read the dissenting opinion below. Evelyn remained living in Oakland after 1920 where she married in 1929. During World War II she enlisted in the Army Nursing Corps.

Born in San Jose, California in 1895, Grace Johnson was the youngest of three children. In 1900 the family moved to Los Angeles where she completed the first year of high school and her father worked as a grocer. Although her elder brother became an architect, the census did not list either daughter in the1910 census as working. Her life took an abrupt turn in November 1918 when the police picked her up three times for “vagrancy” and loitering. Admitted to the isolation hospital under the Chamberlain Act, health officials examined her and determined her to be afflicted with venereal disease. Two weeks later, on December 5, 1918, Grace demanded a writ of habeas corpus. Released on bail, she awaited a hearing scheduled for February 8, 1919. According to court documents, the judge remanded Grace back to the hospital, judged still to be afflicted with the infection. She appealed her case and returned to court on March 12, 1919. to address two specific issues. First, the court justified the quarantine as it would be for leprosy, smallpox, or typhus. Second, the court held that the legal code demanding isolation for those infected was reasonable. Her lawyer stated her arrest was illegal since there was no warrant, but this was also deemed within the law of public safety. The lawyer then argued that the condition was not communicable without direct contact, but that argument also failed. With the appeal’s failure, she returned to the hospital for more treatment and to work. By January 5, 1920, the census documents show she had been discharged from quarantine and lived in a boarding house at 946 Valencia Street in Los Angeles. Fortunately for Grace her fortunes improved, and she married a citrus rancher from Covina, twenty years her senior, about two weeks after the census was recorded. After his death in 1946, she managed the citrus ranch and ran the business.

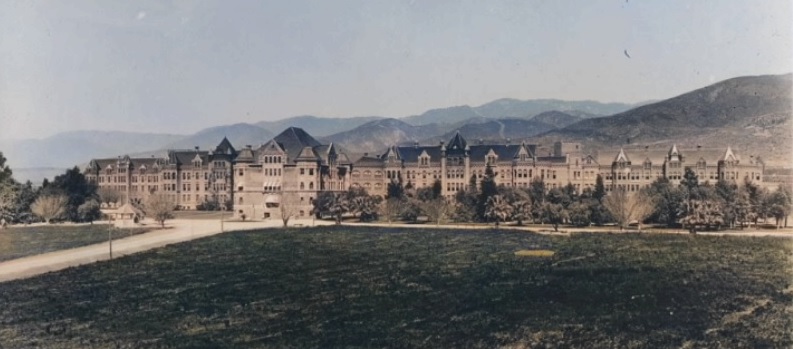

Due to privacy concerns, the photographs are from a professional photographer of the period and are not necessarily the person described in the text.