The Gold Rush may have stimulated a population boom in California, but it was farming that kept them in the state. By 1870 farms in California were too big for one family to harvest so they required migrant labor to tend the crops and harvest them. To meet the need wages for farm labor remained higher than elsewhere in the United States. The first major agricultural crop was grain, and by 1900 the new money maker was the citrus orchards. Unskilled workers streamed to California for work, but by 1910 a new group moved north into the fields. The Mexican Revolution wreaked havoc on the Mexican people and large numbers left the chaos of war for work in the agricultural industry in what is now termed the second wave of Mexican immigration. When World War I broke out many of the young men fought and earned their citizenship. During the Red Scare in 1919 that followed the armistice, the fear of radicals led to efforts to limit immigration, but employers in western industries fought to keep their workers. However, the Depression in 1929 changed the workforce as drought conditions in the Midwest, particularly Oklahoma and Arkansas followed the stock market collapse. By 1932 entire families pulled up stakes and drove west to California to find work. In 1936 the Los Angeles Police Department even attempted to close the border to halt the “Bum Blockade.” The new workers replaced Mexican workers in the fields so many farmworkers returned to Mexico to ride out the Depression. In fact, some cities helped them get bus tickets. However, other workers felt they were being forced to repatriate. As World War II began, the Dust Bowl migrants went to work in skilled manufacturing jobs and agricultural jobs were filled again by Mexican workers. Eventually, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta used the United Farm Workers Union to improve farm worker conditions in the 1960’s.

Header Image: Migrant pea pickers camp in the rain. California, By Dorothea Lange, 1936, from Library of Congress

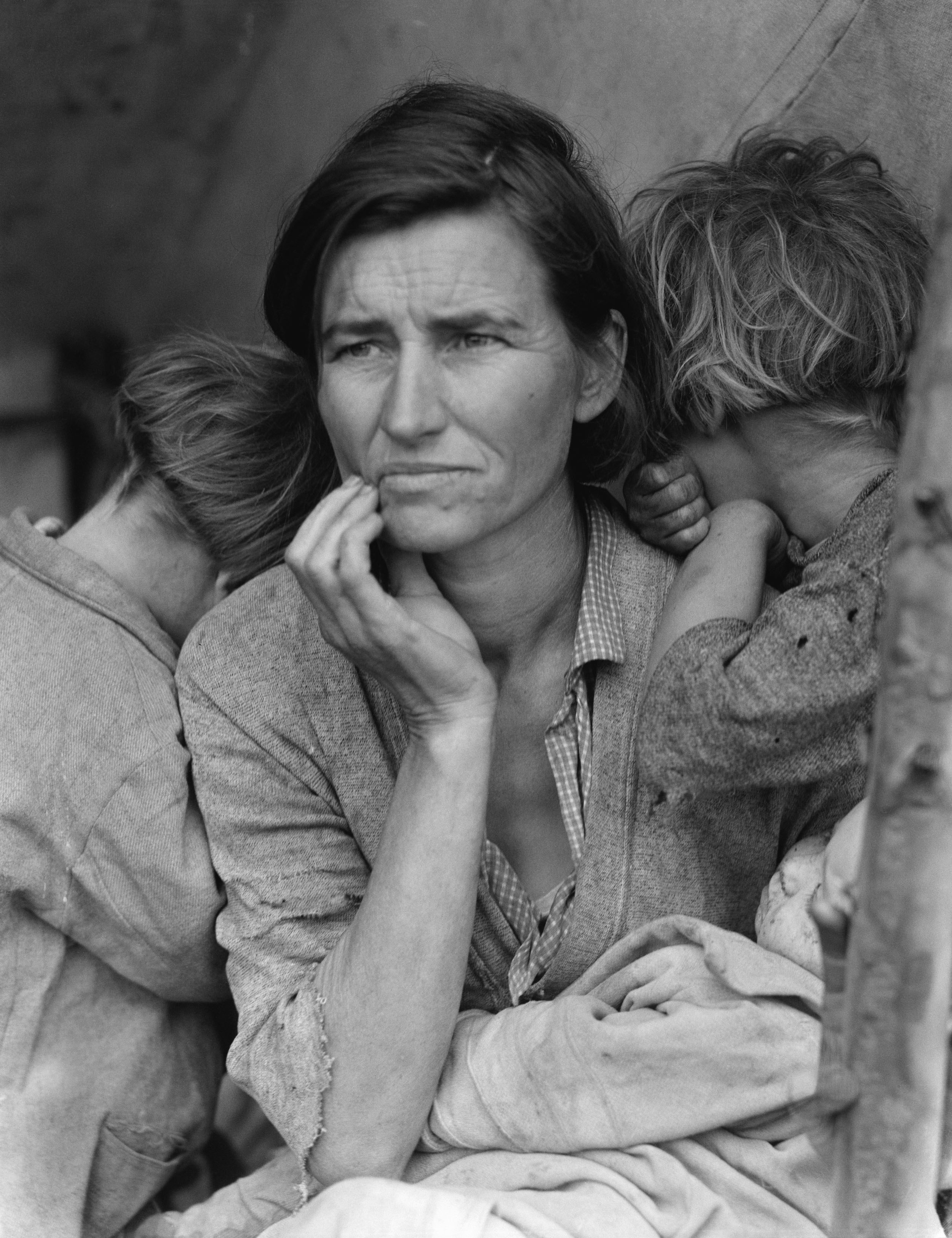

One of the most iconic photographs of the Depression is the one entitled “Migrant Mother.” Taken in 1936 by Dorothea Lange just off the 101 freeway outside of a Nipomo, California pea-picker camp, the face of the thirty-two-year-old woman captured the desperation of the Great Depression. Hired as a photographer for the New Deal program called the Resettlement Administration, Lange was charged with raising the profile of the migrants and stimulating public awareness. Lange herself had two sons whom she placed in foster care so she could chronicle the Depression. The only problem with the photograph was that Lange never asked the woman her name. It was not until 1978 that a reporter discovered the woman living in a trailer park in Modesto, California. The migrant mother was born Florence Leona Christie. Her father, a Cherokee man named Jackson Christie abandoned her mother Mary Jane Cobb before Florence was born in 1903. Her mother remarried a Choctaw man named Akman and the family lived on a farm in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. When she was seventeen years old, Florence married Cleo Owens. Times were hard and they left for northern California to find mill work. In 1931, her husband died of tuberculosis in a migrant camp, leaving pregnant Florence, her parents, and five very young children. She and her parents returned to Oklahoma to find life was no better. While there she gave birth to Charles Welch, the son of a Cherokee butcher. Leaving the baby in Oklahoma, she returned to California where she entered a relationship with Jim Hill. Between 1934 and 1943 she bore three more children. In 1946 she married a hospital administrator, George Thompson. Florence died in 1983 in Scotts Valley, California. Later, when asked about her life, she recalled working from dawn to dusk, harvesting four hundred pounds of cotton a day, serving food, pouring drinks, picking crops. and cleaning up--anything for her kids!

Oral interviews are a wonderful way to capture the story of a person’s life. This is the story of Grace Palacio. Her parents eloped and eked out a living following the rodeo, but the political situation in Mexico had deteriorated since the Mexican Revolution, come to the United States. Grace was born in Jalisco, Mexico in 1920, and soon found herself crossing the border on horseback as they headed for Phoenix, Arizona, with their ultimate destination San Juan Bautista, California. There her father worked in a cement factory and took great pride in his 1928 Chevrolet. She commented that they had no food, but they had a car. By 1929 the plant closed, and the adults did field work every day while the children attended school. By the time she was in seventh grade her father told her to quit school and work in the fields. When she was sixteen years old her mother died of tuberculosis after her tenth child was born, leaving Grace to raise the younger children. Two years later her father’s car broke down and walking home from the bar he was run over by a truck. From then on, all the children worked in the fields or orchards, picking plums or garlic, whatever was in season. Usually, they worked for the Japanese farmers in the area or the Portuguese who went to the Roman Catholic Church with her. As the kids grew up, she hoped to get more education but instead worked two jobs, one at a cannery and the other in the fields. Diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1941, she was sent to a sanitarium. When she left the hospital, she got married and had a son, but another stint in the sanitarium left her feeling like she missed her son’s childhood. In her later years she was an activist for migrant laborers. Recorded in 1977 for the Regional History Project at UC Santa Cruz.

The United States declared war on the Axis powers on December 8, 1941, and the country ramped up to go to war. Farm laborers moved on for higher paying jobs in wartime industries, leaving the crops in the fields. The United States then turned to Mexico as a source of field labor. Once Mexico declared war on the Axis powers, the State Department officially asked Mexico about providing agricultural laborers. Mexico believed that this was away to help the Allied war effort and benefit the Mexican economy. In July 1942 the Bracero program was established by executive order and later made into law in 1951. Although the agreement was expected to last the duration of the war, it lasted until December 1964. The workers were recruited heavily, given identification cards and contracts, and promised that 10% of their wages would be withheld in a Rural Savings Bank processed by the United States and kept in a fund administered by the Mexican government. Here is the story of one man’s experience. In 1945 Quirino Chairez was twenty-four years old. born and bred in Jalisco, the American recruiters came there to pass out work visas for work in the United States. He was one of the first of nearly two million workers who would come to the United States through the program. Given his Alien Laborers Identification Card, he was sent to Midland, Texas to build a railroad. Once that job was complete there were years of others, including harvesting and operating equipment. In the over sixty years he worked, he never visited Mexico for more than a couple of months at a time. In 1995 he became a United States citizen. While he worked 10% of his money was “stored” by the Mexican government. When asked if he ever saw his “retirement” he said, “Nobody did, Nobody I knew.” In fact, many older braceros are in dire monetary straits. Fortunately for Quirino he and spent his later years learning English and living with his nephew in Los Angeles. Others have united to file suit against the Mexican government for the lost wages, Source: Ben Baeder, “Mexican braceros filled need for workers in U.S., Whitter Daily News, April 8, 2006, Updated August 29, 2017.