Persons of African ancestry probably arrived in California with the Spanish, as long ago as 1535 CE when Hernàn Cortez first visited Baja California. Moors from the northern coast of Africa arrived with the Muslims to Spain, while sub-Saharan Africans often served as Black Conquistadores. In addition, many of the first settlers that accompanied the De Anza expedition were of mixed race. In terms of the future state of California the role of African Americans drew attention during the 1849 Gold Rush. Global immigrants raced to join the search for gold, but it was slave holders that brought enslaved workers to the Gold Rush that raised the ire of other miners. They resented that one man could force others to do his work. Due to the Gold Rush, California’s population bypassed territory status and headed for statehood by 1849. Three issues on the topic loomed. First, the two would-be senators from California represented the North/South split in the 1850 United States. John C. Fremont represented the North and as the governor of Missouri during the Civil War issued his own Emancipation Proclamation in 1861. The other senator was William Gwin, and he represented the Southern views as an outspoken slave owner. Second, Peter Burnett became the first civilian governor of California; he grew up in a slave-holding family in Missouri and wrote a law as a judge in Oregon to forbid all those of African heritage to enter Oregon, and later California (California voted it down!). Third, the question loomed about whether slavery should be extended into the new state. According to the 1820 Missouri Compromise, southern California lies south of the 36’30” slavery expansion line, so would be a slave state, however, the majority of the California Constitutional Convention voted it down. Although California entered the Union as a “free state” the Compromise of 1850 that was passed to admit the new state divided the country even further with its reminder of the United States’ Constitution’s 1789 Fugitive Slave Act. (Art.IV.S2.C3.1)

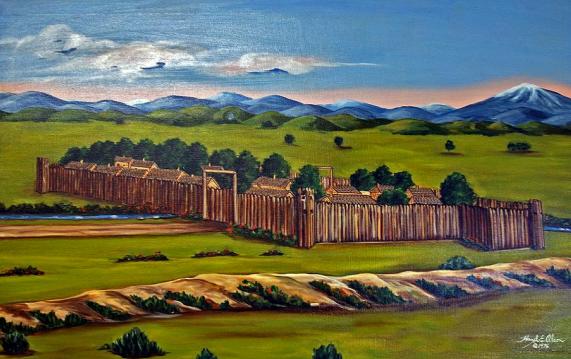

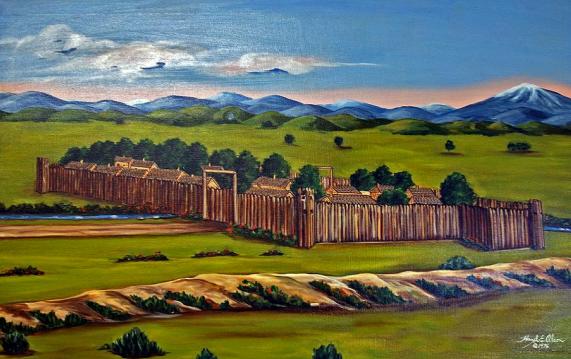

Header image: Fort San Bernardino, By Hazel C. Olson, 1976, from City of San Bernardino

In March 1851, a long line of 150 heavy wagons snaked its way down the Cajon Pass into the valley of San Bernardino, sixty miles from the pueblo of Los Angeles. Their arrival was the idea of one member of the Mormon Battalion, Jefferson Hunt. He often functioned as a guide for gold seekers and encouraged Mormon leader Brigham Young to establish a colony in southern California. Following his suggestion, Young sent 437 pioneers and another twenty-six enslaved pioneers of African descent to buy a Mexican land grant called Rancho San Bernardino that later became the site of the city. Of the two hundred slaveholders who joined the Mormon pioneers one group left South Carolina in 1848 with a fifteen-year-old girl named Lizzy Flake. She walked 1100 miles to Salt Lake City behind the wagons. When her owner died two years later, she and his wife Agnes set out in a wagon on the Cajon trek of 650 miles. When the settlers arrived, they faced a serious threat of Indian attack, so they built the largest fort every built in California for protection. In 1854 San Bernardino incorporated as a city. Lizzy stayed with Agnes and cared for her two young sons, William and Charles. Eventually William returned to Salt Lake City and granted Lizzy her freedom. As more settlers arrived, often bringing enslaved persons with them, the community expanded, despite the fact slavery was illegal in the state. Few settlers paid it much attention until a formerly enslaved man named Charles Rowan told them to go to court in Los Angeles, where the judge granted freedom to fourteen enslaved people. Lizzy eventually married Charles Rowan and together he ran his barber shop, while she raised their children Walter James, Charles, Byron, and Alice and took in laundry. Alice later attended the Los Angeles Normal School (later UCLA) to become the first African American teacher to teach an integrated classroom in Riverside.

Historians still argue over the success or failure of Reconstruction in the post-Civil War South between 1865 and 1877. Some argue that freedom, as imperfect as it was, allowed formerly enslaved persons the ability to choose their partners, raise their children, and reap financial rewards from their hard work. Others argue that Reconstruction was a power grab by northern Republicans, Southern Democrats, and/or greedy capitalists. One man who experienced this change was Robert Stokes; when the war ended, he was eighteen years old. References are made of him as a “freeman” which suggests he was born into slavery in Georgia. Another reference shows his mother, Parthenia Cook, filling out bank documents at the Freeman’s Bank in Atlanta for his older brother. Census documents also place the Cook family in Chattanooga, Tennessee, by 1870. According to family lore, Roberts Stokes took the name “Stokes” from a man he admired named William Stokes with whom he worked or travelled. The census shows him using the name in 1870 and working on the railroad abandoned by Union troops just six years before. The next few years were busy as he married his wife Mary, and set off across the country to Riverside, California. Although he could not read or write he worked hard, first as a laborer and then buying land for his own hog farm. He even ran for office to become the sheriff, called in that county the constable. He stayed connected with his family and encouraged them to move to the land opportunity in Southern California. His nephew David arrived, and he became a part of the burgeoning African American community, owning a store and founding an African American Masonic Lodge. His mother came after 1880 and died in Riverside in 1903. When they decided to dig a sewer in his neighborhood, Mary and he were two of the signers; their “X’ is clearly visible on the document. Perhaps for him the real proof of his success was his registration on the voting rolls of Riverside County every year!

Alfred Summers spent the Civil War in his home state of Virginia, but by 1869 he had started his family and needed a dependable income. In 1866 the United States Army created the 10th U.S. Cavalry, as one of eight all African American regiment, Summers decided to enlist in F Company. Deployed in the “West,” he fought in the “Indian Wars,” and oversaw the reservations. During that period, the indigenous tribes dubbed the regiment the “Buffalo Soldiers.” Initially, the regiment was stationed in Kansas and Indian Territory (Oklahoma), but in 1874 the Regiment moved to Fort Concho in Texas, which served as home base until 1884. Highly effective, they explored 34000 miles of rough terrain, laid telegraph wire and fought the Apache Indians. This was also the period in which Summers learned to survive in harsh terrains. By 1880 he retired from the army. Reconstruction was over but the African American Homestead Act of 1862, along with the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment, still granted African Americans citizenship and the privileges of the Homestead Act including 160 acres for a nominal fee. Just west of the Colorado River cattle ranching and mining were proving successful. By 1910, a former enslaved entrepreneur, William Jones, and his wife Anna, founded the Eldorado Gold Star Mining Company, located in southern Nevada. They posted an ad that was “An Appeal to all Colored Men” to avail themselves of mining and agricultural opportunities in the Inland Empire. Twenty-three Black homesteaders accepted the offer, including Alfred Summers; among the homesteaders were seven women. By 1911, the Lanfair Valley settlement was flourishing as they dreamed of building a “Tuskegee of the West” in their “veritable agricultural empire.” The first several years flourished as the rainfall sustained enough crops to make a profit. However, the dry times set in and by 1946 the town was on its way to becoming a ghost town. Summers moved to Pasadena and died in 1925 at the Sawtelle National Home for Disabled Soldiers in Los Angeles.